On November 11th 2022, Robin Wang, professor of philosophy at Loyola Marymount University gave an online lecture under the title, “Metaphysics Against Aggression: What Rou 柔 (Suppleness) Can Teach Us.” This was the fourth lecture in the “Collaborative Learning” (Si Hai Wei Xue 四海为学) series hosted by the Philosophy Department at ECNU. The lecture was chaired by Prof. Dimitra Amaranditou (Shanghai Normal University), and comments were provided by Prof. Gong Huanan 贡华南 (ECNU) and Dr. Li Manhua (Royal Holloway University of London).

The main aim of Prof. Wang’s lecture was to weave three threads into a coherent whole. The first thread is a textual understanding: Robin Wang understands the philosophy of the Lao-Zhuang texts as one of rou 柔 (“suppleness”). The second thread is an epistemological construction: an understanding of the structure of reality as one of rou. The third thread is a paradigmatic shift: a practical and ethical result of our understanding our reality in terms of rou. These three threads are clearly interrelated. If one may understand the Lao-Zhuang texts as primarily espousing a philosophy of suppleness, then a receptive reading of their philosophy may lead us to understand the world in this way. This takes us to the second thread: the basic makeup of the world is viewed in terms of suppleness and rigidity. If we take such this view, then it has philosophical and ethical implications for how we discuss the world. This is the third thread: we come to understand the power of suppleness, and this in turn affects how we act.

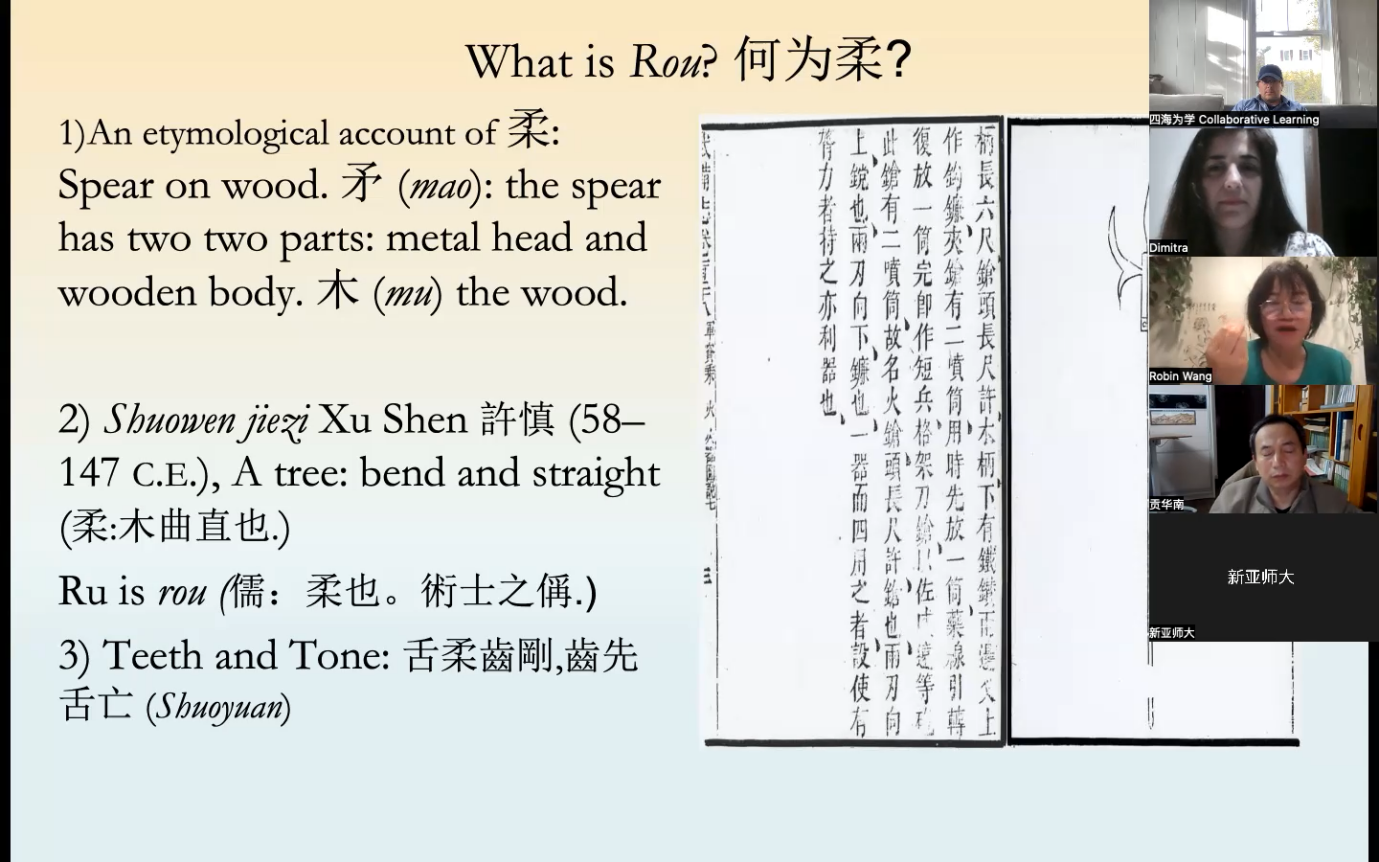

Robin Wang presents the etymological background of the character rou 柔to illuminate some layers of meaning inherent in the term. Wang points to how the character is composed of a spear (mao 矛) on wood (mu 木). This points to the interplay of the hard and the soft. The wood might initially be considered something hard, but when it is acted upon by the spear it reveals itself as something soft and supple. On a more basic level, it shows that our understanding of rou comes from human experience of trees. China’s earliest dictionary from the Han dynasty, the Shuowen jiezi 说文解字 glosses the character as representing the tree in both bent (qu曲) and straight (zhi 直) states. The capacity to move between straight and bent positions is possessed only by what is supple, not by what is rigid and hard. The same dictionary also draws a connection between the character rou and the phonetically similar ru 儒 (“learned” or “Confucian”)—implying that suppleness, or flexibility, is a central motif of the pursuit of literate learning. The primarily Confucian compilation Shuo yuan 说苑, edited by Liu Xiang 刘向in the Han dynasty, contains a discussion of the tongue and the teeth: although teeth are hard and the tongue is soft, teeth fall out while our soft and supple tongues stay with us for our whole lives. This example from human biology may serve as a metaphor for why the Lao-Zhuang texts promote rou over gang 刚 (“hardness”). Suppleness is more conducive to, and representative of, the preserving of life than hardness or rigidness.

This idea about the vitality of rou comes across perhaps most strongly in chapter 76 of the Laozi. It reads, “When alive, men are supple (rou) and soft. When dead, they are stretched out and reaching the end, hard and rigid. When alive, the ten thousand things and grasses and trees are supple and pliant. When dead, they are dried out and brittle. Therefore, it is said: The hard and the rigid are the companions of death. The supple (rou) and the soft, the delicate and the fine are the companions of life.” In this chapter, the metaphor between the life of a tree and human life is especially clear. When one tries to break the branch of a tree that is full of life, one finds it does not snap away. It is full of moisture and sinews that bend and stretch as one pulls and tears at it. The dead branches of a tree are entirely different. They snap easily when pressure is applied. If we consider, then, the character of a person: how much like a tree is it? If one remains hard and unmoving, one tends to come up against more resistance, and one is without effective ways of dealing with that resistance. If, by contrast, one is flexible, supple, and fluid in one’s approach to things, one may withstand a much greater degree of tearing and dragging, both literally and figuratively. A rou response to literal “tearing and dragging,” or physical aggression, is epitomized in the martial art judo, called literally in Chinese “supple way” (roudao 柔道). The techniques involved in its practice are to respond to the force of the opponent and turn it against him or her, rather than doggedly applying one’s own force. Taking “tearing and dragging” in a more figurative sense, we may consider the many ways one might be antagonized in an interpersonal context. Often the best way to respond to a snarky email, for instance, is not to come back with equivalent aggression but to bend ironically to the antagonism one has received.

The discussion of the tree exemplifies how Robin Wang weaves together the three threads of textual interpretation, epistemological construction, and ethical paradigmatic shift. The textual is the interpretation of the centrality of rou in the 76th chapter of the Laozi. The epistemological construction is the understanding of the makeup of the world in terms of the interplay between hardness and softness, whether this is in the domain of the human world or that of trees. Finally, the paradigmatic shift comes with the realization that establishing ourselves and maintaining our vitality does not mean imposing ourselves on the world. Rather, a supple responsiveness to what we meet is more conducive to our flourishing. In the space between these three threads lies the mind. This is what understands the text, interprets the world, and determines our course of action. In this regard, Wang draws attention to the heart/mind as whirlpool (xinyuan 心渊). Wang quotes chapter 8 of the Laozi which says, “for the mind, competence lies in deep water.” In the Zhuangzi, the same image of deep water is used in connection with stillness (jing静). A mode of knowing by rou constitutes a “synthesis of possibility and necessity.” It is a mode of knowing that includes non-knowing, that embraces uncertainty.

The first comments and questions on the lecture came from Prof. Gong Huanan (ECNU). Gong Huanan is the author of several works on the important place of “flavor” (weidao味道) and “taste” (weijue 味觉) in Chinese philosophy. Speaking more broadly, Gong’s work investigates the role of different senses in different traditions of philosophy, noting that vision is perhaps the prominent mode of sensing in the Western tradition. Vision is strongly related to the notion of clarity, whereas other senses like taste, hearing and touch are less conducive to producing precise descriptions. Gong notes that Wang’s treatment of knowing the world through rou (rou zhi 柔知) places a large degree of emphasis on the sense of touch. Wang pointed out in her lecture how knowing the world through rou involves a holistic mode of knowing through proprioceptive sensors in the body. In this mode of knowing, all the perceptive organs help to situate the body in space.

The second set of comments and questions were delivered by Dr. Li Manhua (Royal Holloway University of London) and focused on a widely debated topic in contemporary philosophy, among other fields, namely environmentalism. Li pointed towards the capacity of rou in helping understand better our relationship with our environment. In addition, Li commended Prof. Wang’s interdisciplinary approach, which took in research and findings outside of philosophy, especially from physiology. Li’s questions help us to reflect on an important contemporary issue, as well as important philosophical challenges in understanding our relationship with nature.

We may even ask, when viewed from the Lao-Zhuang philosophical perspective that expounds the interconnectedness of all things, if there even exists an entity “nature” that can be defined by its separateness from humans.

Report by Rory O’Neill

学校主页

学校主页 校内链接

校内链接 校外链接

校外链接 校内邮箱

校内邮箱