On December 9th 2022, Stephen Angle, professor of philosophy at Wesleyan University gave an online lecture under the title, “Growing Moral: Living as a Progressive Confucian in the Twenty-First Century.” This was the fifth lecture in the “Collaborative Learning” (Si Hai Wei Xue 四海为学) series hosted by the Philosophy Department at ECNU. The lecture was chaired by Prof. Li Jifen 李记芬(Renmin University of China), and comments were provided by Prof. Lisa Indraccolo (Tallinn University) and Prof. Fang Xudong 方旭东(ECNU).

Prof. Stephen Angle discussed in his lecture what it is like being a Confucian in 21st century America. A primary focus in this way of life is the idea of moral growth. The education we receive as adults today is typically with a view to becoming successful in our careers. The focus of our education is instrumental: it guides us in accomplishing things that will give rise to some benefits, typically material or reputational gain. What Prof. Angle teaches his students is not instrumental to some external end but pertains to an inherently valuable aspect of our lives—how to be people. The subject of Angle’s teaching is thus set apart from what his students learn in their other courses. Nevertheless, responses from his students make clear that there is a pressing requirement for this kind of education. One student described his course as “the most relevant” of all her courses. The fact that this student did not describe it as relevant to anything in particular is most telling. The implication is that it is not narrowly instrumental, but relevant for living her life.

Prof. Angle’s project is ambitious in its scope. His Confucian philosophy aims to take in the broadest possible range of the Confucian tradition. This spans from the Duke of Zhou in the 11th century BCE, through the time of Confucius living in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, through debates of Mengzi and Xunzi in the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE respectively, taking in the Neo-Confucianism of Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming of the Song and Ming dynasties, and leading all the way to the “New Confucianism” of these two centuries. The result of this broad scope of textual and historical resources is, perhaps surprisingly, a large degree of freedom for personal interpretation. Not being confined to any one thinker or period, Angle is vested with a certain amount of freedom to find what he sees as the deepest currents of the Confucian tradition. Within this vast stretch of history, Angle finds the elements of Confucian philosophy that are most relevant to the circumstances he and his students find himself in contemporary America. Meanwhile, some parts of Confucian history and aspects of the thought which we might see as oppressive to certain members of society, most notably women, might be viewed in light of a more inclusive overarching celebration of all people in society and the promotion of harmony between people.

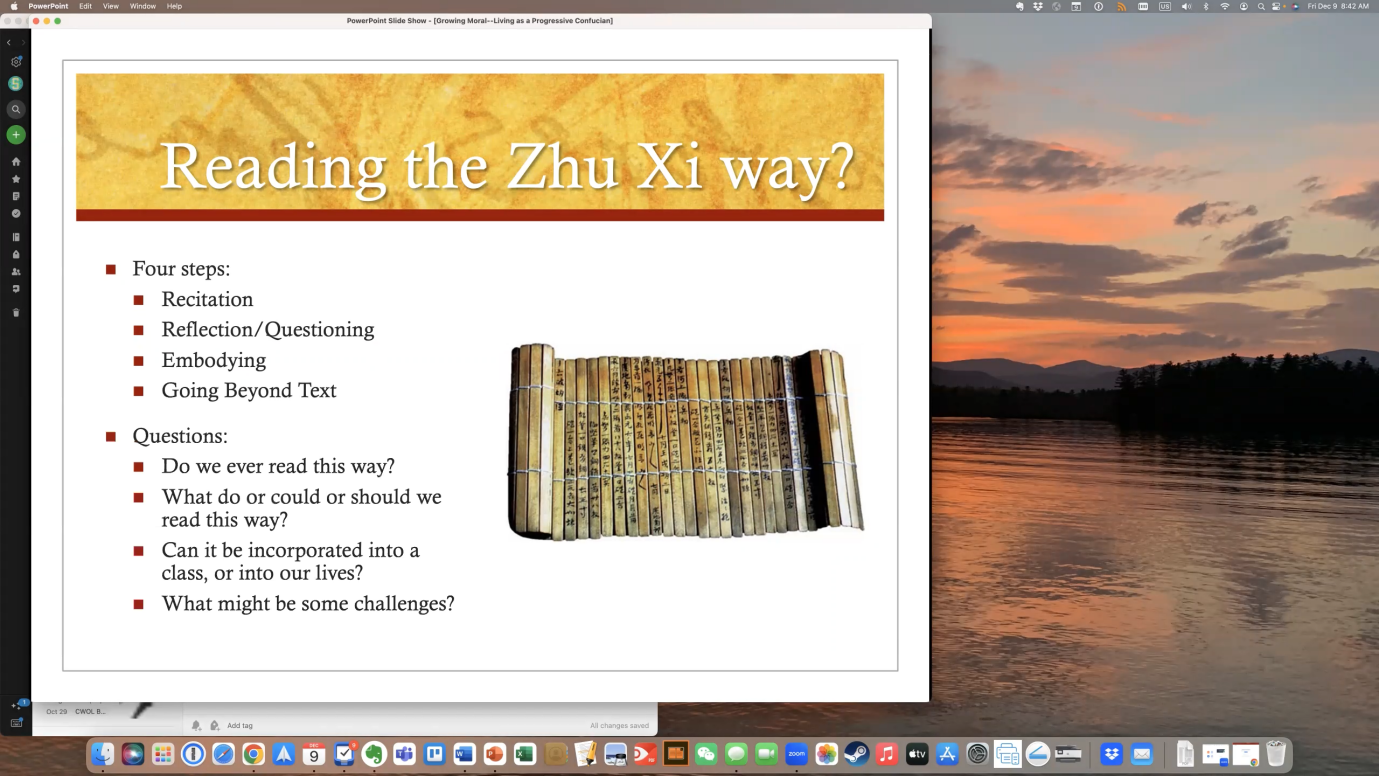

Given the historical scope of Angle’s focus, he chooses one practical aspect of the tradition to focus in on, thereby revealing its value and applicability for us today: the Confucian practice of reading. Reading is something that every college student is very familiar with, yet here again a distinction is made between the kind of instrumental reading encouraged in most college courses—i.e., reading for the purposes of passing a test or completing an essay—and reading as a practice that has its own intrinsic worth. Angle refers to this reading practice as “reading the Zhu Xi way.” It involves a process of internalizing the text through repeated recitation. Once the text becomes familiar enough, we engage in reflection and internal questioning. This leads to our embodying the texts: the text is no longer something external to us, but something that is bound up in our very being. The text responds to how we think and act, just as our thoughts and actions respond to the text. This process leads us beyond the text. What is important is no longer the text itself, but the process of moral growth of which the text forms a part.

Reading the Zhu Xi way aims to maintain faithful engagement with the text without giving way to scholastic pedantry. The latter would obstruct our capacity to derive meaning from texts, while the former is a necessary component in ensuring we appreciate their value. While the critical mindset encouraged by higher education is a necessary trait for engaging successfully with these classical texts, a certain degree of humility is also required. A critical approach should not be too rash in deriding a classical text as “not making sense” before the text has been given ample opportunity to speak to us. This is part of the task of being faithful to the text—it requires a degree of patience and generosity. Provided this faithfulness to the text is achieved, we should not be afraid to engage critically. This is what makes the texts more than mere objects for dry scholastic observation. Striking this balance is perhaps the most central concern for Angle’s project and one that he encourages his listeners to discuss. It is clear from the enthusiasm of Angle’s students, readers, and listeners that he has been successful in his application of these ideas to our contemporary circumstances. But does Angle’s work faithfully reflect the Confucian spirit? Or, in his words, is it “just a hodgepodge of Western ideas dressed up in Chinese clothing”?

The response from Prof. Lisa Indraccolo was testament to the enthusiasm in the Western context for what Angle calls “New Confucianism.” It is clear that Confucianism is not merely a historical object to be studied, but alive as a contemporary philosophy. The male dominance in the history of the Confucian tradition cannot be denied. However, we now live in a very different society from the vast majority of the periods from which Angle draws his resources. The deeper currents of Confucianism that allow for equality between women and men are evident in the very fact that the tradition speaks to women today and has relevance to how all people in society conduct our relationships.

The second set of comments and questions came from Prof. Fang Xudong who is also heavily involved in modernizing the Confucian tradition. His response constituted a celebration of Angle’s work while also raising some key challenges. We may take a progressive approach towards the Confucian tradition, but to what extent can we push it? Do we risk losing the tradition if we bend it too much to our contemporary requirements? Another key question relates to the scope of textual resources with which Angle is working. While this broad range of material may provide much in terms of inspiration, if there is no particular focus then it may be difficult for other scholars to engage by exchanging interpretations of particular texts.

The lasting impression from Angle’s talk is an inspiring modernization of a rich tradition. Prof. Angle’s work encourages all of us studying classical Chinese texts today to feel part of a living tradition, and not observers of lifeless artifacts.

Report by Rory O’Neill

学校主页

学校主页 校内链接

校内链接 校外链接

校外链接 校内邮箱

校内邮箱