On January13th 2023, Franklin Perkins, professor of philosophy at the University of Hawai’i gave an online lecture under the title, “On ‘Doing What You Really Want’” which drew primarily on the Chinese classical text Mengzi 孟子. This was the sixth lecture in the “Collaborative Learning” (Si Hai Wei Xue 四海为学) series hosted by the Philosophy Department at ECNU. The lecture was chaired by Dr. Li Ting-Mien 李庭綿 (University of Macau), and comments were provided by Professor Ping Zhu (University of Oklahoma) and Professor Tao Jiang (Rutgers University).

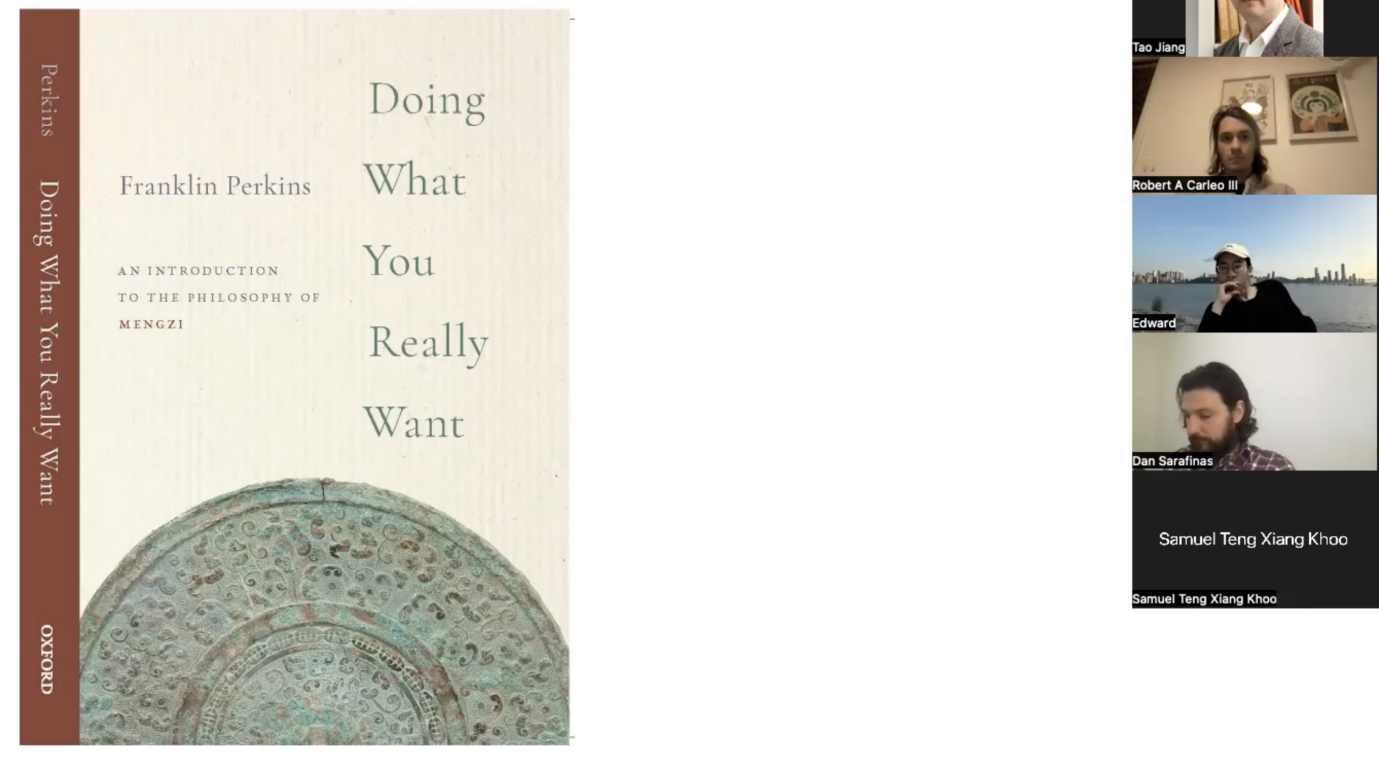

Prof. Franklin Perkin’s lecture focused on the question of doing what we really want, drawing on the classical Chinese text the Mengzi as his prime philosophical resource. According to Perkins, this text—named after the master associated with it, also known as the Mencius—holds that no contradiction exists between doing what we want for ourselves and doing what is good for society. One obvious challenge to this view is that some people seem to want to rob banks, or commit murders or sexual offenses. To this, Perkins tells us, the Mengzi’sresponse would be that these actions are not what such people really want to take. It is merely the case that these people are not adequately cultivated, and are therefore ignorant of what they really want.

Choosing to do what is right should be no different from choosing the food that one wants to eat. The example given in the Mengzi is the choice to eat bear paw, apparently a delicacy in ancient China, over fish. Bear paw is simply the more desirable food, and therefore one would choose to eat it over fish. However, some cultivation of taste may be required for one to want the bear paw over the fish. Note that in such an instance, it is probably not because one has acquired facts and thus knows that bear paw is the better choice. Rather, it is because of cultivating ones taste that one wants the bear paw. it is a cultivated decision rather than an informed decision. Similarly, for Mengzi, the most important thing is not to gain knowledge of the right thing to do. It is to cultivate one’s person so that one wants to do the right thing, whether that be in the family, in ones work, or as a political leader.

The main motivation, Perkins tells us, for the Mengzi’s focus on what we want is that it responds to the emphasis found in the Mozi 墨子 on private benefit, or “profit” (li 利), as the motivator for people to act correctly. Mengzi sees this focus on profit as unnecessary in that it assumes a division between one’s own personal benefit and the benefit of the whole society. Such a manner of thinking may even be detrimental as it diverts attention from the reality that what is good for society as a whole is good for me too. If people fall into the profit driven trap of thinking, especially the political heads of society, then they may seek personal profit at the expense of the benefit of the kingdom, which is in turn detrimental for those leaders too.

Doing the “right” thing means doing what is best for the whole of society, or for all people. And this will ultimately be best for the individual too. This is a rejection of the selfishness/altruism dichotomy. This dichotomy is one that is fed to us from many sources, including from Christian teaching. The Christian Bible teaches to love thy neighbor, and while the Bible itself might not necessarily treat the altruism of caring for one’s neighbor as in tension with attending to oneself, it is often interpreted thus. Accordingly, selfless behavior will be rewarded only in the afterlife, and might be detrimental to one’s worldly wellbeing. In contrast to this assumption, Perkins supposes though that no good philosopher would accept a simple dichotomy between altruism and selfishness and especially not one versed in Chinese philosophy, as they would be no doubt be familiar with the concept of the relational self. If, as is the case with the relational self, there is no hard distinction between self and others, then there is certainly no hard distinction between care for others and care for the self.

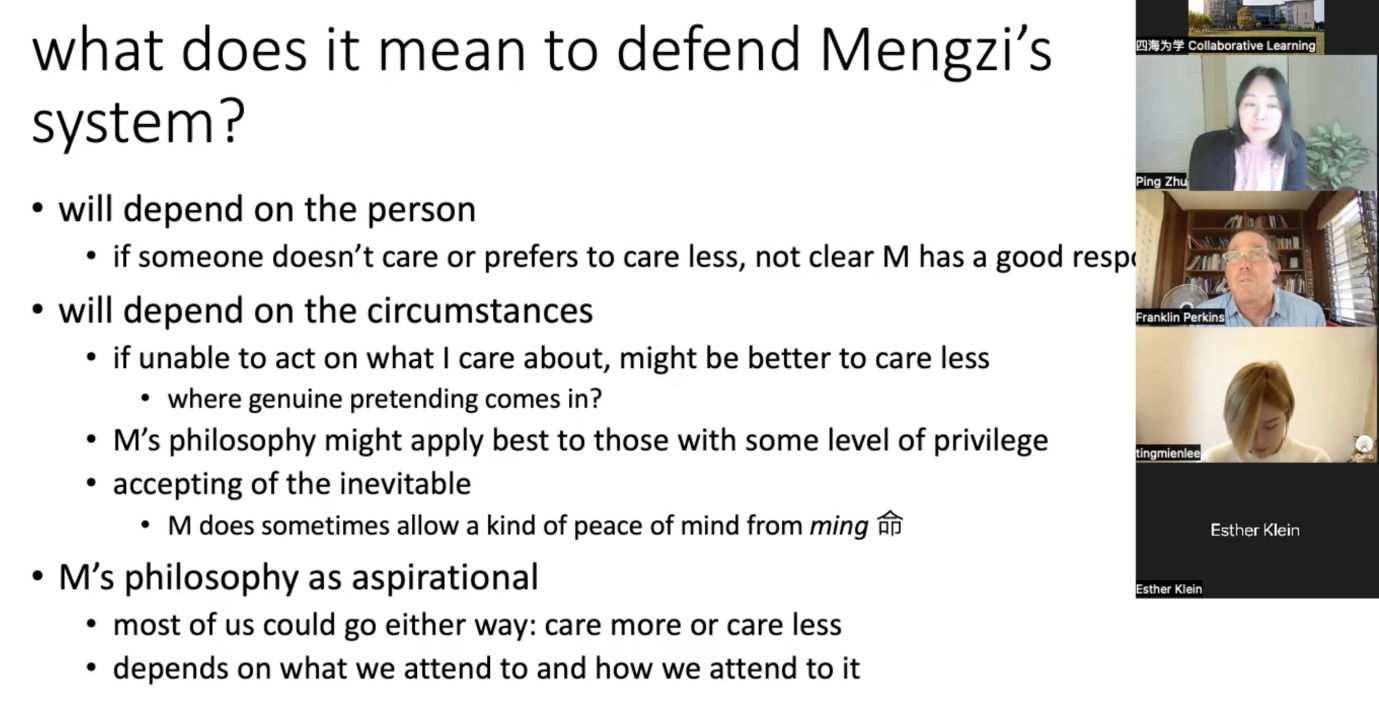

While from a historical perspective it is much more likely that the Mengzi is responding to the Mozi than the philosophy of the Zhuangzi 庄子, a text which took form long after the Mengzi, Perkins finds it valuable to compare the Mengzi with Zhuangzian philosophy too. While the Mengzi is representative of a philosophy of caring, the Zhuangzi supports a philosophy of carefreeness. Aside from the question of whether what we really want is also what is good for others, and not just our private benefit, it is also worthwhile questioning the importance of caring, of wanting. In some cases, the better option for our wellbeing might be detached acceptance of a situation, rather than profound care for it (think of tedious tasks like filling in administrative forms). Rather than teaching how one should cultivate wanting, as in Perkin’s reading of the Mengzi, the Zhuangzi warns us of the dangers of this kind of conditioned wanting. In Perkins’ view, while the latter might be a good philosophy for when we find ourselves in those situations where there is not much meaning in what we do, it does not offer the same level of fulfilment as doing what we really want.

In thefirst set of questions and comments, Prof. Ping Zhu sets this philosophy in the context of our modern society. In the era of modern capitalism, businesses encourage us to discover what it is we want, and to go and get it, or do it. On the one hand, this phenomenon alerts us to the dangers of cultivating people as “wanters.” On the other hand, discovering what it is we really want is perhaps a means of getting past these trivial desires to discovering what is more meaningful. Finally, Prof. Tao Jiang points out how the word “really” is doing a lot of the “heavy lifting,” so to speak, in Perkin’s phrase “what you really want.” He asks, what function does this adverb have? Where does it come from? Who or what stipulates what we really want? On this point, Prof. Perkins returns to the importance of the people around us. What we really want is what is right, and what is right is what is good for all of society. And when good comes to society it will bring good for us individually as well, whereas personal benefit for some individual in that society might only bring discord, and may therefore eventually lead to trouble for that person who benefitted. So, doing right for others really is what we really want!

Report by Rory O’Neill

学校主页

学校主页 校内链接

校内链接 校外链接

校外链接 校内邮箱

校内邮箱