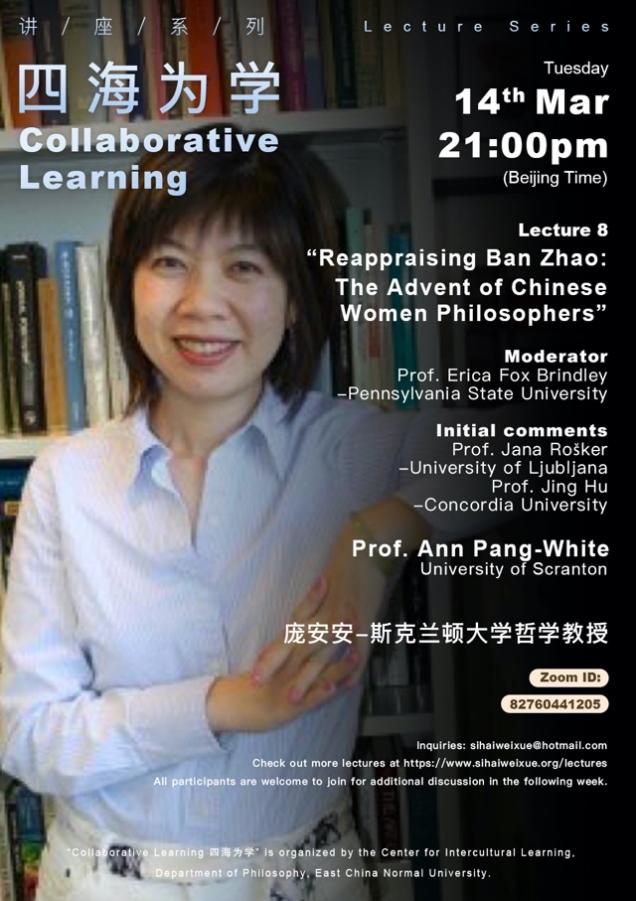

On March 14th 2023, Ann Pang-White, Professor and Director of Asian Studies at the University of Scranton (Pennsylvania, USA) gave an online lecture with the title, “Reappraising Ban Zhao: The Advent of Chinese Women Philosophers.” This was the eighth lecture in the “Collaborative Learning” (Si Hai Wei Xue 四海为学) series hosted by the Philosophy Department at ECNU. The lecture was chaired by Prof. Erica Fox Brindley (Pennsylvania State University), and comments were provided by Prof. Jana Rošker (University of Ljubljana) and Prof. Jing Hu (Concordia University).

In this talk, Professor Pang-White set out to rehabilitate the reputation of Ban Zhao 班昭, the first female philosopher and historian in the Chinese tradition. While an accomplished scholar, Ban Zhao has been criticized for the conservatism and sexism of her views, most scathingly by He Zhen 何震, the 20th-century Chinese anarchist feminist. Ban Zhao finished the History of the Han汉书, the official dynastic history of the Western Han, and was also the author of the Lessons for Women女诫, which was one of the first books in the world about women’s conduct written by a woman. While the “lessons” presented in the book are quite conservative by today’s standards, Professor Pang-White argued that they are in fact quite radical for their times. First, the text seems to advocate for monogamy, which was not the norm at the time (well-off men were expected to take concubines). Second, it promotes women’s education and views women as capable of attaining the virtue of ren仁 (human excellence). Third, in discussing the relations between husbands and wives, it puts some of the responsibility for upstanding conduct on the men and states that wives should not be flattering towards their husbands.

Other works by Ban Zhao also complicate any overly dismissive view of her. In a poem, “Rhapsody on Needle and Thread” 针缕赋, Ban Zhao uses a metaphor of sewing to discuss how public officials should act, providing connection between women’s work and virtue rarely seen in the Confucian tradition. Furthermore, she courageously risked her life to make a request to the emperor to bring her brother back home, who in old age was still serving in the Western regions. Professor Pang-White hopes that by being read in the context of her time, some of Ban Zhao’s more feminist and radical aspects can come to light.

After Professor Pang-White’s talk, Professor Rošker provided comments. Professor Rošker noted that while the Lessons for Women is the most conservative of the Confucian four books for women 女四书, it is one of the first, if not the first, work to explicitly advocate for the education of women. By contrast, the Book of Rites礼记states that only male children should be educated. Lessons for Women also began work on eliminating the patriarchal prejudice that claims that women can be talented but not virtuous. Therefore, it indeed includes some radically progressive and even revolutionary ideas. Professor Rošker was interested in how Ban Zhao’s work can be seen alongside the Daoist tradition, which, in both practice and theory has been more egalitarian with respect to women. Professor Rošker also wondered what Professor Pang-White considers Ban Zhao’s main contribution to contemporary feminist discourse to be.

Professor Pang-White discussed how bringing Ban Zhao into contemporary discourse can help to diversify transnational and global feminism, which is often viewed as including only a limited set of voices. In a global context, Ban Zhao appears more progressive than some later thinkers, such as Rousseau. With regard to the Daoist tradition, Professor Pang-White stated that Daoist and also Buddhist philosophy are resources to revise Confucianism, but given the dominant position of Confucianism in Chinese society, she wants to work within Confucianism first.

Professor Fox Brindley asked about how a philosophy that relies so heavily on ritual and playing your proper role can be adapted or reinterpreted in a nonpatriarchal fashion. Professor Pang-White noted that flexibility is built into Confucianism, although the tradition later rigidified. Even in the Book ofRites, important rituals can be deviated from according to needs of the circumstances. Other Confucian texts to which flexibility is more central, such as the Book of Changes易经or Book of Poetry诗经, should not be forgotten. And as noted, Daoism and Buddhism can also be used as resources for reform.

Later, conversation turned to differences between the Confucian four books for women. Professor Pang-White discussed how the Lessons for Women and also Teachings for the Inner Court内训were written for aristocrats, and the language is therefore harder to read than some earlier texts like the Analects论语. The most progressive of all the texts, by far, is the Short Records of Models for Women女范捷录. It’s author, Liu Shi 刘氏, was from the south and included women like prostitutes who are usually excluded from discussion in such texts. It also discusses how the female way of thinking is superior to that of the male in situations that demand urgency and flexibility.

Report by Henry Allen

学校主页

学校主页 校内链接

校内链接 校外链接

校外链接 校内邮箱

校内邮箱