On September 16th 2022, Roger Ames, professor of philosophy at Peking University gave an online lecture under the title “The Confucian Concept of the Political and ‘Family Feeling’ (xiao孝) as its Minimalist Morality”. This was the second lecture in the “Collaborative Learning” (Si Hai Wei Xue 四海为学) series hosted by the Philosophy Department at ECNU. The lecture was chaired by Prof. Sydney Morrow (University of Central Oklohoma) and comments were provided by Prof. Zhang Rongnan 张容南 (ECNU) and Prof. He Jing 何静 (ECNU).

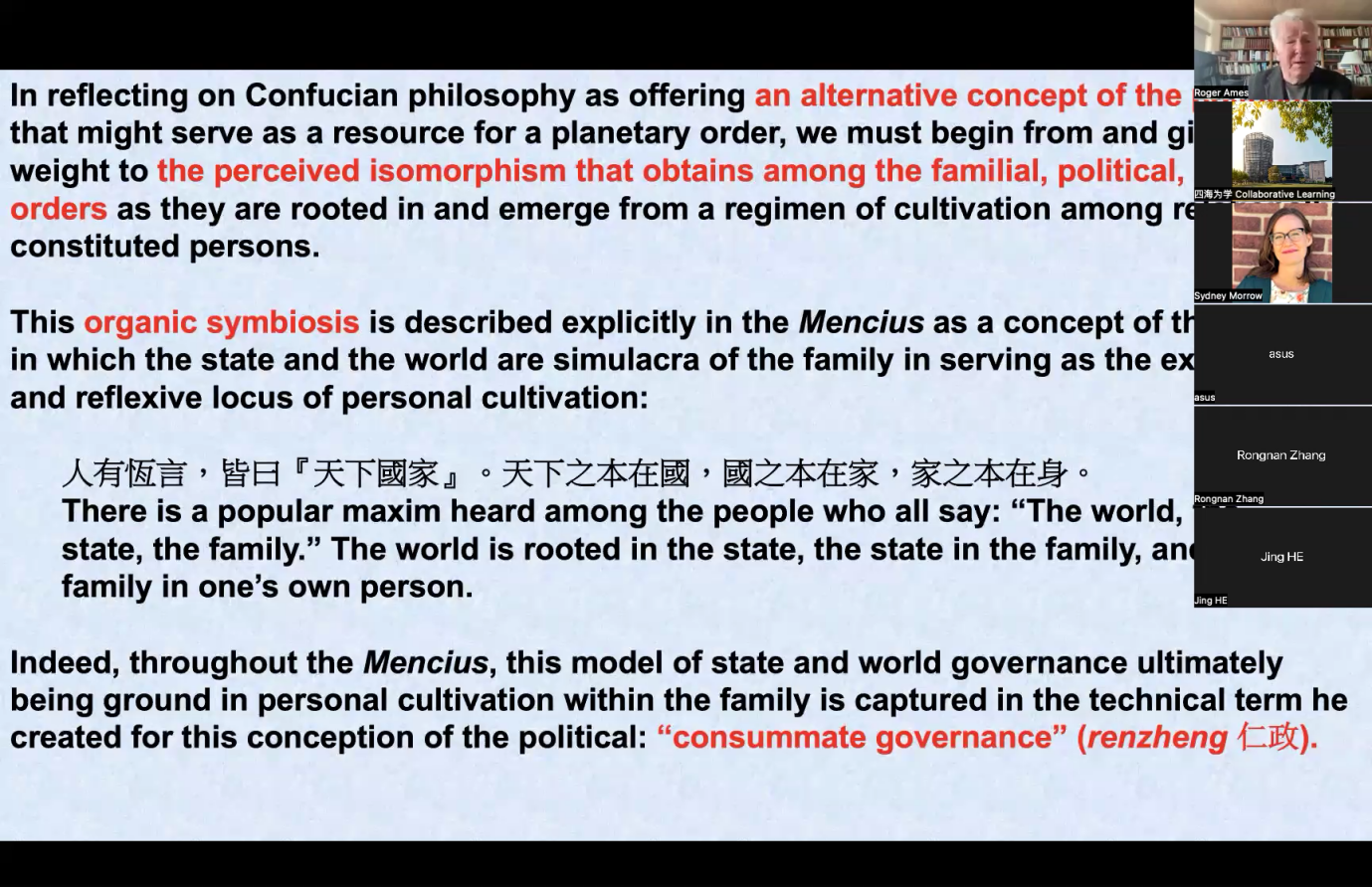

In the spirit of “collaborative learning,” let us begin our discussion of this lecture with an exchange it inspired between Professor Ames and Professor Zhang. Following the lecture, Professor Zhang raised a common concern with the mixing of politicaland family: should the political not rightly belong to the public sphere, and the family to the private? For the Confucians, Professor Ames explained, these are not separate. The sense of justice we learn at home helps us to navigate the public realm. The “family feeling” (xiao 孝) that is cultivated at home helps us feel out how best to treat others. Interpersonal relationships are not uniform, but infused with that family feeling, whether the relationship is between mother and daughter, teacher and student, or political leader (jun 君) and minister (chen臣).

John Rawls famously encourages us to step behind the “veil of ignorance” and come to an idea of justice that upholds a blindness to all partialities and biases. Instead of inviting us to cover our eyes with a veil, Roger Ames invites us to look out our faces in the mirror. We may find looking back at us the features of our grandmothers. In approaching a sense of justice, is it better to recognize those feelings that arise from seeing our grandmother? Or is it better to cover our eyes with a veil that makes us make us blind to those particularities? By recognizing the significance of the particular, Ames’ minimalist morality does not propose a model of governance that takes a set family structure from one context and imposes it universally. Rather, he draws our attention to that which is already alive within us. He speaks with Elizabeth Wolgast, who in turn draws on Ludwig Wittgenstein, in saying that concepts such as Justice are “forms of life.” This is an approach which starts from what is most real and apparent. It “sets the root” (zha gen 扎根) in order to “grow from there” (shengzhang 生長) with appropriate caution and trepidation.

When Ames proposes “family feeling” (xiao 孝) as a minimalist morality, he seeks to begin with particulars. He draws on Michael Walzer who emphasizes the importance of “moralities created here and here and here,” Robert Soloman who emphasizes paying attention to local considerations and Elizabeth Wolgast whose community-based conception of justice begins at home. These thinkers are united by a reluctance to derive morality from pre-existing theories or ideals, recognizing instead that morality is derived from feeling. They each recognize that justice is a form of life. In keeping with an approach to theory taken by John Dewey, theorizing responds to practice and experience—it is something that comes after experience to make it more intelligible and intelligent, rather than something that determines it. The “family feeling” that Ames views as a candidate for a “thin” universal morality is not one that should be imposed, but rather one that he sees as already operative in the broadest swathe of human experience. It does not demand that we reach a consensus on some pre-determined proposal. Ames returns to the Latin root of the word “consensus”: shared (con-) feeling (sentire). Rather than stipulating specified feelings or actions, it seeks to unify people by means of what is already shared. In the words of Confucius, as taken from the Analects, “Exemplary persons seek harmony not sameness” (junzi he er bu tong 君子和而不同).

Roger Ames proposes that “family feeling” is not just a minimalist morality, but a universal one. Special attention should be paid to how it should be considered “universal.” We are encouraged, in the words of the Laozi to “view all under the sky from the perspective of all under the sky” (yi tianxia guan tianxia以天下觀天下). The “thatness” of morality as a specifically experienced meaning is crucial to Ames’ approach. This means for all of us, including for China, thinking from the perspective of each member of the world community. For those outside China, that includes thinking about China from a Chinese perspective. Necessary for this is education. To understand each other, we must learn to appreciate how we are different. Arriving at an appreciation of what is shared by learning particulars is to appreciate the “continuity in change” (bian tong 变通).

Family feeling is a way of getting past the us/them binary. It relies on what is different—what is particular to all of us—but when we appreciate this difference, we realize its inclusive appeal. Bernard Williams illustrates this by presenting a scenario of two people drowning in a river. A man passing by could only save one, and when asked why he chose the one he did, he responded, “Because she’s my wife.” According to Williams, this explanation needs no elaboration, as the significance of the family tie speaks for itself. This anecdote emphasizes the concrete reality of each situation—the significance of the particular relationships that are at play in almost every human interaction. Williams’ example reveals how behind the myriad particulars is a commonality: the choice to save one’s family member requires no explanation. This discussion gives an insight into what Walzer means by a minimalist morality that is “close to the bone,” and it is for this reason that the morality cultivated in family has a greater capacity for harmony than the blind justice of legal systems. Family teaches us the wisdom of interdependence. Family feeling has the potential to move us beyond a zero-sum approach towards striving for well-being.

If “family feeling” is indeed something that is already shared in the broadest swathe of human experience, if it does exist as particularities “here and here and here,” then what is the point of speaking about it at all? If it accommodates all differences, is it not totally vacuous? While it does not stipulate, it does challenge us to reflect, and the impact of this must be observed and experienced in practice. To understand this, we must take a Deweyan approach of learning by doing. The “family feeling” that Ames speaks of can be observed in the Collaborative Learning (Si Hai Wei Xue 四海為學) program in the way in which participants are encouraged to interact. While we are striving together towards academic progress, we also recognize that this progress takes place among people. Interpersonal feelings and the respect derived from them are part of the collaborative learning experience.

Report by Rory O’Neill

学校主页

学校主页 校内链接

校内链接 校外链接

校外链接 校内邮箱

校内邮箱